Did the natural realm have a cause? It would seem that the answer must be either yes or no. Let’s consider first the implications if the answer is no. In other words, what would it mean to say that the natural realm has no cause?

If nature had no cause, then there are two options available to us. The first option is that nature began to exist without a cause. The second option is that nature has always existed. Religious people reject both these options. Both options seem, not merely improbable, but downright unintelligible. Both options—uncaused existence and eternal existence—defy our everyday experience and our most fundamental intuitions about how things work.

I understand why religious believers have such negative reactions to both these options because I have precisely the same reactions, though I do not presume that my incredulity amounts to a refutation. It may, as far as I know, be possible for something to occur uncaused. Sometimes quantum mechanics is cited in support of things happening without a cause, but I address in my book Religion Refuted why this is a mistake.

The notion that nature could have occurred uncaused is shocking. It defies our everyday experience. But when we start talking about nature itself, I’m not sure that our everyday experience, restricted as it is within the scope of nature, is relevant. Every bit of evidence that we have tells us that things come into existence only when caused to do so, but every bit of that evidence derives from within nature and therefore cannot tell us whether causes exist outside nature. In fact, no one has ever credibly explained how to distinguish the boundary between the natural and the supernatural.

To my mind, the notion of nature being past-eternal is even more shocking than nature being uncaused. If nature were past-eternal, it would take an eternity to get to the present moment. Put another way, an infinite number of moments must have elapsed. But infinity is not a number. Infinity is essentially an unbounded counting process. While an unbounded process is not inherently illogical, the notion that such an unbounded process can ever be completed is profoundly illogical, and that seems to be precisely what is implied by the notion of nature as past-eternal.

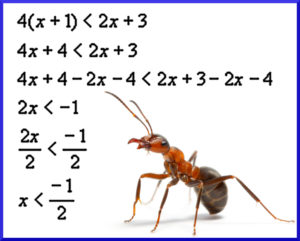

Maybe I am missing something, but this argument against nature being past-eternal strikes me as about as compelling as any argument can be. Then again, does my inability to comprehend nature as past-eternal prove with certainty that nature must be past-finite? Perhaps not. After all, the human mind did not evolve to ponder such things. Neurological limitations imposed on what I can believe may not reflect restrictions on what nature can do. Maybe I can’t imagine past-eternity for the same reason that an ant can’t imagine algebra. In that case, I am no more qualified to deny that nature is past-eternal than an ant is to deny the existence of algebra.

At this point we have considered two options, namely that (1) nature was uncaused and (2) nature is past-eternal. As mentioned above, the potential that nature is uncaused is incongruent with my experience within nature, while the notion that nature is past-eternal seems to defy logic. So, let’s examine the one remaining option, namely that the natural realm has a cause. I’d love to discover that this third option provides relief from the intellectual turmoil triggered by the other two options.

Unfortunately, I think we run into equally insurmountable difficulties with this option. The hypothesis that nature had a cause is plagued by its own brand of incoherency. The concept of causation makes no sense unless the cause precedes the effect. I will grant that there are some apologists and perhaps even a physicist or two who have argued that causes do not always have to precede effects. William Lane Craig, for example, has cited the Aristotelian proposal that causes and effects can be simultaneous.

But if you were to argue that an effect can occur simultaneously with its cause, then you have raised a new puzzle. How would you tell which is the cause and which is the effect? If they occur simultaneously, then what’s to prevent an event from being its own cause? In my book Religion Refuted, I discuss these and other difficulties that arise from the notion of simultaneous cause and effect.

Let’s suppose that we agree that causes must precede effects, as accepted by virtually all physicists. In that case, causation cannot occur except within the flow of time. Since time is a component of space-time, causation occurs within some space-time context. But if there is space-time and causation, then aren’t we still speaking about the natural realm? It seems to me that we are. This means that the option of nature having a cause, despite its initial plausibility, is ultimately incoherent.

This leaves us in a bad situation. The question as to whether the natural realm has a cause has no satisfactory answer. No matter what answer we propose, that answer invariably leads us into some kind of intellectual quandary. Moreover, even if the objections against these various options were resolved, we’d still be left with a mystery, at least until we actually come up with some hard evidence in favor of one of these options.

Our inability to answer the question about whether nature has a cause does not mean that there is no answer to the question. It means only that we humans lack the ability to answer this question. We have confronted the limits of our current knowledge and perhaps even the cognitive limits of our primate brains.

Rather than fight one another under bogus sectarian battle flags, we should have the honesty and the intellectual integrity to embrace our pitiable state. We are small creatures in a big, mysterious universe. Let us deal fairly with one another and proceed with the humility our situation warrants.